Era una cálida mañana de sábado del verano de 1994. Yo estaba trabajando en Big Red Software, un desarrollador de videojuegos con sede en Southam, Warwickshire, justo al final de la calle de Codemasters. Naturalmente, ya habíamos jugado a Doom, que se había lanzado unos meses antes y seguía siendo el juego más popular del mundo. Nuestro programador Fred Williams compró una copia de la versión shareware en la tienda Game de Leamington High Street; se podía descargar gratis, pero en aquel entonces Internet era muy lento y muy caro, a diferencia de Game, que era cómodo y muy caro. De hecho, una de las decisiones comerciales más inteligentes que tomó John Romero fue permitir que las empresas de software con canales minoristas ya establecidos empaquetaran y vendieran Shareware Doom sin costo alguno desde Id Software. Permitió que el juego se volviera viral en un momento en que «volverse viral» todavía significaba contraer varicela en la fiesta de cumpleaños de tu pareja. Como el disco no tenía protección contra copia, casi tan pronto como Fred lo llevó a la oficina, estuvo en las computadoras de todos. Estábamos enganchados.

Pero después de algunas semanas de juego todavía había una cosa que no habíamos probado: el modo multijugador. Doom se lanzó con lo que ahora se consideraría un modo en línea muy básico. Admitía el juego entre pares a través de módems de acceso telefónico o podía vincular hasta cuatro jugadores a través de una red de área local. Como desarrolladores de juegos, teníamos uno de esos. Eso es lo que hicimos ese sábado por la mañana. Nos pusimos a trabajar para conectar nuestras PC a través de la LAN de la oficina y jugar unos contra otros por primera vez.

Llegamos a las diez de la mañana planeando un par de horas de juego. Aunque en aquel entonces no existía un sistema de emparejamiento o lobby, no fue tan difícil de configurar. «Nos conectamos a través de IPX LAN», recuerda Williams. «Sólo tenías que ejecutar su programa de instalación, decir que estás haciendo un juego LAN para X player en su pequeño programa de configuración en modo texto de DOS, esperar a que todos hicieran lo mismo y se iniciaba automáticamente cuando había tantos jugadores. »

Conocíamos el brillante diseño de Doom. Pero de lo que no nos dimos cuenta, hasta que empezamos un juego cooperativo para cuatro jugadores, fue cómo se sentiría compartir este extraño mundo con amigos: ver sus avatares en la pantalla luchando contra diablillos, volando en pedazos al explotar. Tambores de aceite. Tienes que intentar recordar que los mundos virtuales compartidos eran materia de ciencia ficción en ese momento. Había algunos juegos de igual a igual para dos jugadores, pero este era un juego de disparos visceral ambientado en una base espacial en ruinas. Este era el dominio exclusivo de William Gibson y Neal Stephenson, Star Trek Holodeck y Tron. En realidad, no se suponía que íbamos a ir allí nosotros mismos.

Fred era el jugador más experimentado y hábil, avanzaba a toda velocidad, despejando espacios. Estaba deambulando asombrado, como un flaneur que explora el París del siglo XIX, pero con una ametralladora. Tenía esos momentos en los que llegaba a una repisa, miraba y veía a Fred y Jon en la distancia descargando escopetas contra un enorme Cyber Demon, escuchándolos a ambos gritar desde la habitación al final del pasillo. Fue absolutamente fascinante, completamente nuevo. Según el programador de Id, Dave Taylor, esta alegría ruidosa también estaba ocurriendo en Id Software. «Se trataba de Deathmatch», dice. «Especialmente con Romero en la habitación. Era jodidamente divertido. Tenía insultos tan hermosos, y cuando lo mataste, soltó gritos de agonía tan satisfactorios. Y me hizo preguntarme, ¿a cuántas otras personas les va a gustar ese tipo de cosas?» ¿de insulto/agonía, charla de combate a muerte?

Resultó mucho. Incluso antes de su lanzamiento, se estaba replicando en todo el mundo de los juegos. «El momento en que me di cuenta de que Doom iba a ser enorme fue cuando hice un viaje de regreso a [my old workplace] Microprose en noviembre antes de su lanzamiento», recuerda Sandy Petersen, codiseñador de niveles. «Se lo mostré a mis antiguos compañeros de trabajo y se volvieron locos. Simplemente no podían creerlo. Les dejé una copia previa y más tarde escuché que retrasó varios juegos hasta por seis meses.

«Y lo que más escuché de otros desarrolladores fue: ‘Oh, nunca nos dejarían hacer un juego como este, es demasiado violento’. Y luego, por supuesto, un par de años después, de todos haciéndolo.»

No tengo ninguna duda de que la explosión del género FPS tras Doom fue el resultado de decisiones comerciales; después de todo, generó millones de dólares. Pero creo que el deseo técnico, la capacidad de crear juegos en red en la era anterior a la banda ancha, provino de estudios como el nuestro que jugaban a LAN Doom en nuestro tiempo libre (o en el tiempo de trabajo) y querían, sin necesidad, descubrir cómo funcionaba. y cómo podría replicarse. Un año después, Modem jugó en nuestro propio juego, Tank Commander, y estoy seguro de que nuestras sesiones de Doom allanaron el camino para ello.

«A todos nos sorprendió lo avanzado que era el juego para esa época», dice Jon Cartwright, entonces programador en Big Red y ahora consultor de diseño de videojuegos en Australia. «Por supuesto, la tecnología tenía sus limitaciones, pero como cualquier buen juego simplemente cedió ante las limitaciones y empujó tan lejos como pudo. Recuerdo a Paul [Ransom, Big Red’s MD) saying that this kind of engine was the future and we needed to build one. It was not too long after that we ended up getting dddWare and went on to build Tank Commander and Big Red Racing. Doom was incredibly specialised and really only rendered vertical rectangles as well as flat floor polygons. And of course, like Wolfenstein all the enemies were 2D sprites with a bunch of frames. But they looked fantastic, and as horrific as they needed to, and critically everything that Doom did was very, very efficient in a time when 3D accelerator cards weren’t around.»

Id Software also made another seemingly eccentric decision which turned out to be genius – they ported Doom to Unix and a range of Unix-like operating systems. This was the shared computing platform used in serious workplaces throughout the world – now it ran Doom multiplayer. «That was responsible for getting it into the visual effects and scientific communities, which was kind of an interesting side effect,» says Taylor, who handled a lot of the Doom conversions. «At the time, Unix workstations were like today’s modern operating systems. It was the barely tolerable solution for computing for scientists, and they just would never look down their nose at Dos. It would just be like, I’m not going to subject myself to that. I have a PhD.» But getting these geeky communities onboard via the LAN mode was instrumental in growing the audience for the game and ensuring its dispersal. When I ask Taylor what the scientists were doing with Doom, he shrugs his shoulders. «I don’t know, science shit? They just happened to be on Unix workstations because they had to do these fancy simulations of things. I think they were just avoiding work with Doom just like everybody else.»

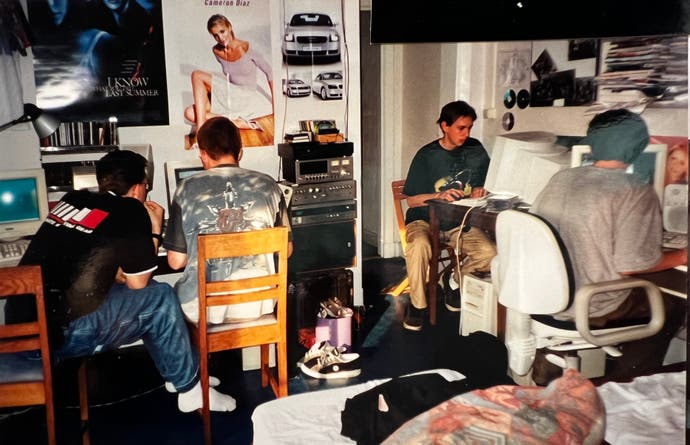

Hours flew by at Big Red. Outside the closed blinds, night was drawing in, but we didn’t notice. We started on Deathmatch and the vibe changed – it was more tense and emotional. That sense of real human competition. After a few hours, we were all developing different styles of play revolving around different weapons. We’d all played two- and even four-player local multiplayer games on home computers and consoles before, but this was something new – competing in first-person in a 3D space, with a range of weapons and an architecturally complex environment – it required new skills, new conventions – a new language almost. It felt like a whole new universe opening up. And the fact that a LAN was the easiest way to play Doom as a multiplayer game, meant that gamers had to get out and meet.

Doom didn’t invent the LAN party concept, but it gave it a big kick up the router ensuring that it ruled the competitive gaming scene in the late-90s and early 2000s, As Taylor recalls, «We had this really compelling multiplayer format that forced you to come together in a LAN party. Well, there’s your social network! You’re coming together, forming the party, now you’re socialising. and that concretes the bond. tIt wasn’t everybody that was doing this multiplayer stuff, but God damn, it was a stunning amount of people. And so we were really knitting together these communities.»

That was it, I think. That was what it felt like – that we were at the very start of this new global community of game players. Playing Doom over a LAN was happening to me at the same time as I was discovering Usenet and online forums. Later, the Dwango service made it possible to play Doom over the internet (well, kind of, it was a long distance dial-up service.), and this expanded the experience even further.

A year later, our own 3D war game, Tank Commander was deep into development when Paul Ransom signed a deal to support the new CyberMaxx VR headset. They sent us a sample and it was decided that some idiot in the office had to test it out – that idiot was me. Tank Commander wasn’t quite ready, but Doom was one of the headset’s launch titles so I tried that. The Cybermaxx was an enormous and uncomfortable headset and its two eyepieces seemed to poke right into your skull. Also, it was doing VR in 505×230 resolution with significant lag. But still, there was Doom once again, showing everyone the future – at least that’s what I was thinking 20 minutes later while vomiting profusely into the office toilet.

I feel kind of sorry for the generations of gamers beneath me, who have had broadband all their lives. They will never know the wonder of stepping into a hellish space station and seeing their friends in there too, and this being something totally new and arcane and wondrous. When I finally left the office very late that night, I felt differently about games and what they could do. I felt that, in some small way, I had to be a part of it. Thirty years later, I still am, and so is Doom.